I am, at best, an Instagram

psychologist. Sure, I've read a couple books. I've been to some therapy. I can synthesize some of my life experiences into something like lessons for myself. Yet I'm a person perpetually dumbfounded by my own

existence, and I haven’t made much "sense" out of it.

It's

the realization of lostness and smallness coupled with the insatiable

and even destructive urge to attempt expression that makes artists and writers into

artists and writers, almost beyond our own will. Little thrills and

validates me like mudlarking my own head to "forge delicate air into words, giving them wings as angels of persuasion and command," as Emerson put it. Before persuasion or command, though, is connection. Expression opens the door to connection, and connection is life force.

Connecting over celebration and rejoicing tastes sweet! But total fumbling greed is what I feel for connection over things dark, sad, and difficult to

know. Forging that delicate air into words is what magnetizes me to art. To write - to share - is to fight against cosmic loneliness.

The zeitgeist of 2022 and 2023 in the United States is complex and I am a fool whose errand it is to attempt an explanation. Memes are the startling language of our lightspeed era. I can't always decipher meme genres. Am I seeing the bestsellers or the indie releases or the dark web chatter? I bet a brilliant linguist is writing a book about this now, including the hierarchy of meme sources and its meaning; depending on your age, you are most likely to gravitate toward specific social media platforms or websites, which determines how far removed you are from meme incubators. That's why your older friends send you memes you saw three weeks ago and your kids use terms you've never heard.

I feel goofy describing meme incubation with such seriousness, but the life of a language is the pulse of culture. The word "meme" was coined by evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, conceptualized around 1976. The term is a hybrid of the Greek mimema, meaning "that which is imitated," and the English "gene." Memes as we know them today didn't exist in 1976, but the concept of a thought virus - the social imitation of a resonate idea - is an essential component of what makes us feel digitally connected.

The internet, memes, and language move faster than humans develop. That's why we eventually stop socializing on newer platforms. Xanga, Myspace, Tumblr, and DeviantArt were my teenage haunts, then I found a groove on Facebook, but settled on Instagram. Twitter, Youtube, and Reddit are of the same era (perhaps a fraction later), but their visual layouts were poor, overwhelming, or both. Snapchat was the first platform I rejected based on the sense that my ability to assimilate had expired, and I refused to learn TikTok even when my employer asked me to.

Let's liken those eleven platforms to international dialects that were born within the past fifteen years. The seismic shift in language and culture is impressive enough, but consider that our children will speak ten other dialects! Does the internet (and language) change us or do we shape the internet (and language)? Both. Neither. Sometimes one, sometimes the other. I don't resist that major swaths of our lives are irrevocably digital. Instead, I want to equip my children to know and practice art and relationships within the framework of our global digital language.

What, then, am I to make of the microcosm of memes that are my present language? In simple English, I'd describe them as shockingly funny and depressing at the same time. I'll call it oxymoronic mystic nihilism, and there's no marked exit.

***

Rewind to 2020. I experienced pockets of super-human functionality during the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. Don't impale me for using the past tense, the general feel seems to be that the health crisis component is alleviated. Yet it's clear that it's left permanent marks beyond our lung tissue.

Throughout 2020 and 2021, I was on constant high alert about the minutia of

daily-changing health advice and the reality that "the truth" of how to

best handle COVID was often undecipherable or plain unknowable. I don't know if there was one single day for 1.5 years that I didn't have some discussion about health protocols. I remember likening it to a Jenga tower, wherein each adjustment touched every other aspect of my physic structure.

Meanwhile, I saw the landslide in my children's mental

health as they were ripped out of their entire outside lives and then suffered through whatever was happening with Zoom school (along with their teachers, Lord have mercy!). Then there was the engulfing drama of grocery shopping and masking politics. Three years on, grocery shopping remains a source of anxiety for me, though I used to look forward to it. The list goes on. There were people dying everywhere, every day. That was true before COVID, and remains true, but our awareness of our vulnerability and our potential to imperil others was sustained and acute.

You were there too. I know you must have your own painful, perhaps as-yet-untold

stories of the chaos and horror visited on the whole world,

sometimes of our own making. I begin to get an idea of how archetypes like The Angel of Death come to be. We felt our faces pressed against the glass of our powerlessness in the scheme of everything, and we closed our eyes, or cried.

I'm good at survival. I'm very tough when I need to be, and my brain and body have needed to be a lot

more than I anticipated, even while the material aspects of my life are better now than they were ten years ago. Humans tend to respond to stressors with fight, flight, or freeze reactions as self-preservation strategies. These reactions to real or perceived threats cause a surge of adrenaline in the human body, and we need to recoup that energy expenditure through rest. The need to recoup rest coupled with the lack of opportunity to do so explains a lot of the 2022-3 meme flavor.

When we don't know how to rest - and our society works against us here - we may continue to respond with "freeze," which we subliminally hope makes us invisible to danger, like our friends the possums. Did you know the common possum lives only two years? The freeze response really takes a toll.

The signs of collective PTSD are visible. I saw that unprofessionally, of course, but something is happening. I was born with RBF, but not anxiety, depression, or ADHD, that I'm aware of. Are we getting better at diagnosing, or is this a silent second pandemic? To be clear, many of us were struggling a-plenty prior to COVID, but I think it's unspoken yet uncontested that we've entered a new phase of psychosomatic wasteland that follows survival (sometimes beautifully!) of an apocalypse. I know you know this teetering feeling I'm getting at. It often feels like we're on the brink of not making it.

Again, my analysis is anecdotal, but I think we're seeing a surge in the divorce rate. Did the pandemic cause divorce or separations? Of course not. But prolonged stress, loss of income and housing, illness, upheaval of all kinds, and inability to soothe oneself so as not to exacerbate interpersonal conflicts? Definitely. Crises can be a time of clarity, and I hope each of us is on the frontlines of supporting our friends and family who make a break from destructive dynamics. I also celebrate the bonds that held, in spite of everything. It's a little bit miraculous, mysterious, maybe even ludicrous.

During months of lockdown and then forming pods, I became much closer with my closest friends. Then I moved far, far away, priced out of my hometown as the job and housing markets fell ill with capitalism. There were other factors too, I'm sure, but by mid-2022, I lost the ability and most of my will to socialize. That sounds so extreme, but I know from memes and from short chats with friends that the experience is rampant. Because the language of the internet has some consistency, it's been a genuine aid in maintaining a sense of self and adjusting myself. It's our place to feel lost, together. A constant distraction as well as a ceaseless call-in. To frame social media as a mere highlights reel ignores that it gives us words, often memed, to grieve, be scared, and begin to recover.

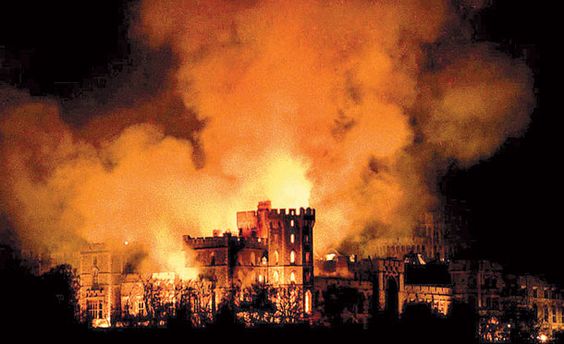

Face to face (if you can coax me from my home-cave), I'm no longer who I was in 2020, but neither is anyone else. I'm braver and more scared. I'm mortally wounded and hopefully wiser. I'm bent and twisted like a lawn chair wrapped around a palm tree after a hurricane. Wrung out after disaster. The world as I knew it is gone and it's never coming back. Grieving takes longer than the time given us, and change doesn't wait for grief to subside.

I've never been in a hurricane, but I can imagine that if you've lived through the full force of a massive storm, even a breeze can be triggering. That's how 2022 socializing felt. It felt unsure and unsafe. I was unsure of myself when I used to be confident. I was rattled to hear myself talking "too much" with people I didn't know. I talked about death rituals in different cultures at a kid's birthday party, and then I went home and worried that my social skills were Neolithic. Every proverbial breeze pushed me to panic, zero to sixty.

One of my sisters is severely allergic to cats, and I have a cat (long story). Intense allergies can be a life threatening chronic illness. My sister has medication that protects her from death, but coming out of the hyper-vigilance-of-health we learned in coping with COVID into a severe allergy situation punches all my neuroticisms right in the suprasternal notch. I can't not be woefully anal about it because it feels like a continuation of small mundane choices about my clothes or my handwashing habits meaning life or death for my loved ones. Both my sisters are Zen saints for remaining kind and sane while living with chronic illness.

I used to do whatever the living version of rolling over in my grave is when I'd hear about someone dying from ingesting a trace amount of peanut on a candy wrapper. Death by a microscopic amount of allergen is tragi-comic and misérables, like every death. Even for those of us to cling to the hope of a transcendent afterlife. Death may not be the end, but it is an end.

I thought I'd breath easier, no pun intended, with the initial learning curve of COVID behind me. Instead, I was disoriented beyond recalibration. Many standards - the things by which we measure "normal" - were destroyed. Things that felt firm were washed away. I was adrift.

Monsoon, by Raghubir Singh

***

One of my writing heroes is Jean

Stafford, who won the Pulitzer prize for fiction in 1970. It's an award almost always

granted during an artist's lifetime and Stafford was very much alive when she won

this prestigious honor for her work. Yet I happen to know from reading some

biographical material about her that she was plagued for most of her life by

the feeling that she wasn't a good writer and no one liked her.

Pearl S. Buck is another woman in my writer's pantheon and her autobiography harbors an array of tragedies. Buck won the Pulitzer prize for fiction with her very first

novel, The Good Earth, in 1932. She recounted that another writer advised her

not to mind the jealous hatred of her colleagues who thought her undeserving of the Pulitzer for her debut work (they were all men, do with that tidbit what you will). How could she be so good as a virtual novice? She may have been a novice to the literary world, but she was no novice at life by that time.

I have a sizable collection of illustrated children's books and enjoy

learning about the lives of my favorite artists. Many beloved illustrators were deeply strange people, isolated or even ostracized in their

childhoods. It is common, especially among those who also wrote the books they were illustrating, that these artists didn't begin their best work until they'd

retired from their "regular" careers.

Writing in a way that touches

people to the core - even if the writing is very simple - is a skill that

demands a lot of life be lived. And with much life, there is often much

suffering. Not everyone maneuvers the canals of suffering with the same rudder, but when I pay attention, the artists I admire most are talking about the suffering - and the triumphs - of their lives in a way the rest of us understand, even if we don't realize the quiet nod to humanity that we're absorbing.

Part of my own navigation of suffering in the past several years has been breaking open my beliefs about what happens before and after life as we know it. We are unconscious of our own existence apart from the years between our birth and death, but have you noticed how some children share the wisdom of elderly artists? I think that some children have spirits that preexist their bodies, in the same way some older adults allow their spirits to recall infancy. Ouroboros. Jesus often urged adults to embrace their inner child, incidentally a popular practice in modern psychology.

Her consuming pain and self-doubt prevented Jean Stafford from believing in what others recognized in her as

genius. Genius is, I think, a practice of making our experiences more than the sum of their parts. I'm not a masochist, but I'm not sure you can have genius without wounds. Genius is not celebrity.

What most struck me about the movie "Everything Everywhere All

at Once" was how it embodied the 2022 feeling of lost-in-chaos. It captured how we attempt to reach toward one another across the universes of our heads, our families, our private life, and public life, and sometimes fail spectacularly. Even succeeding hurts so much. It was an artful and complex moving meme of genius. Appendix A: Bo Burnham's "Inside" and Phoebe Bridger's subsequent cover of "That Funny Feeling."

***

As I've been drafting these thoughts, 7.8 and 7.5 earthquakes decimated southern Turkey and northern Syria. I know that people die untimely deaths all over the world, every day. For whatever reasons, some hurt worse than others. I find myself open to the grief swirling across my screen on these days more than I have been for a while.

The internet encourages empathy in some of us, despite what talking heads warn. But growing up on the internet means we're connected to all, at all times. We're experiencing everyone's pain at all times, in ways we didn't have access to even 10 years ago. This access illuminates our powerlessness to take individual action that results in global comfort. But what's also clear, if you want to see it, is that we can take collective action that results in local comfort.

The exception to lack of global-scale impact and a boone of localized care is art. Words carried on wings of persuasion and command are needed genius in collective grieving.

Standing on the edge, crying, is an honest response. The Kingdom of God, in which we really love every neighbor, is clashing with the world we've destroyed through not caring about one another. It seems quite natural that this collision, this oxymoronic nihilistic mystic space, renders us shredded mulch for the cosmos. Not as punishment, but as the birthing pains of All Great Loves.

I like to learn about what I'm experiencing as much as the next person, but all psychology is cultural and of its time. Learning why I'm feeling something or the name of whatever thing my brain is doing is interesting, but it doesn't sooth the experience. Everything is not okay just because I learned to label it. Mysticism saying that everything is at once knowable and unknowable is horse shit when you're in the thicket of suffering. If Richard Rohr never freaks out or if Jesus never sweat blood, I might write them off.

The religion of my youth taught that feelings were trickery. If ever I felt them in full, shame bit at my heels because I was enthroning my own experience instead of casting my woes on a Bigger Than Feelings God. Never mind that a person without feeling is a godless husk. If you operate on the belief that your emotions are invalid because everything everywhere all at once is, in fact, bigger than you, you have indeed been tricked. Feelings can change,

but that doesn't mean they don't "count" at the time they are felt.

On New Year's day in 2022, an organization I'm deeply invested in began a fraught and painful

transition away from the leadership of the founding couple, who turned out to be charlatans.

I felt humiliated that I was duped, as if my feelings led me astray and led me

to trust, when cynicism would have saved me a great deal of heartache.

Instead, I felt, and I felt it all. The sentence that brought it all into searing focus for me was, when on their way out, one of the founders said, "this organization isn't about the feelings of the workers." So I spent 2022 helping shape the shreds of our collective into something that honors the feelings of the workers, so that we can work together with Christ to bring a healing Kingdom to earth (Romans 8:29).

Many of us are struggling psychologically more now than we were when the news was ablaze with COVID. We are flailing. It somehow feels lonelier and more exhausting than being shut inside for two years. At least then, I could separate the known and controlled inside from the unknown uncontrollable outside. We're allowed out now, but we've forgotten how to go, and we're scared. I'm nostalgic for the days in which everyone was unmoored at once and no one denied it. Now we are more like ghosts of our former selves, haunting the internet with our lust for comfort.

Listen: our fears, our worries, our sorrows are worthy of being felt, and worthy of our respect.

I've got you, and I've got memes for you.